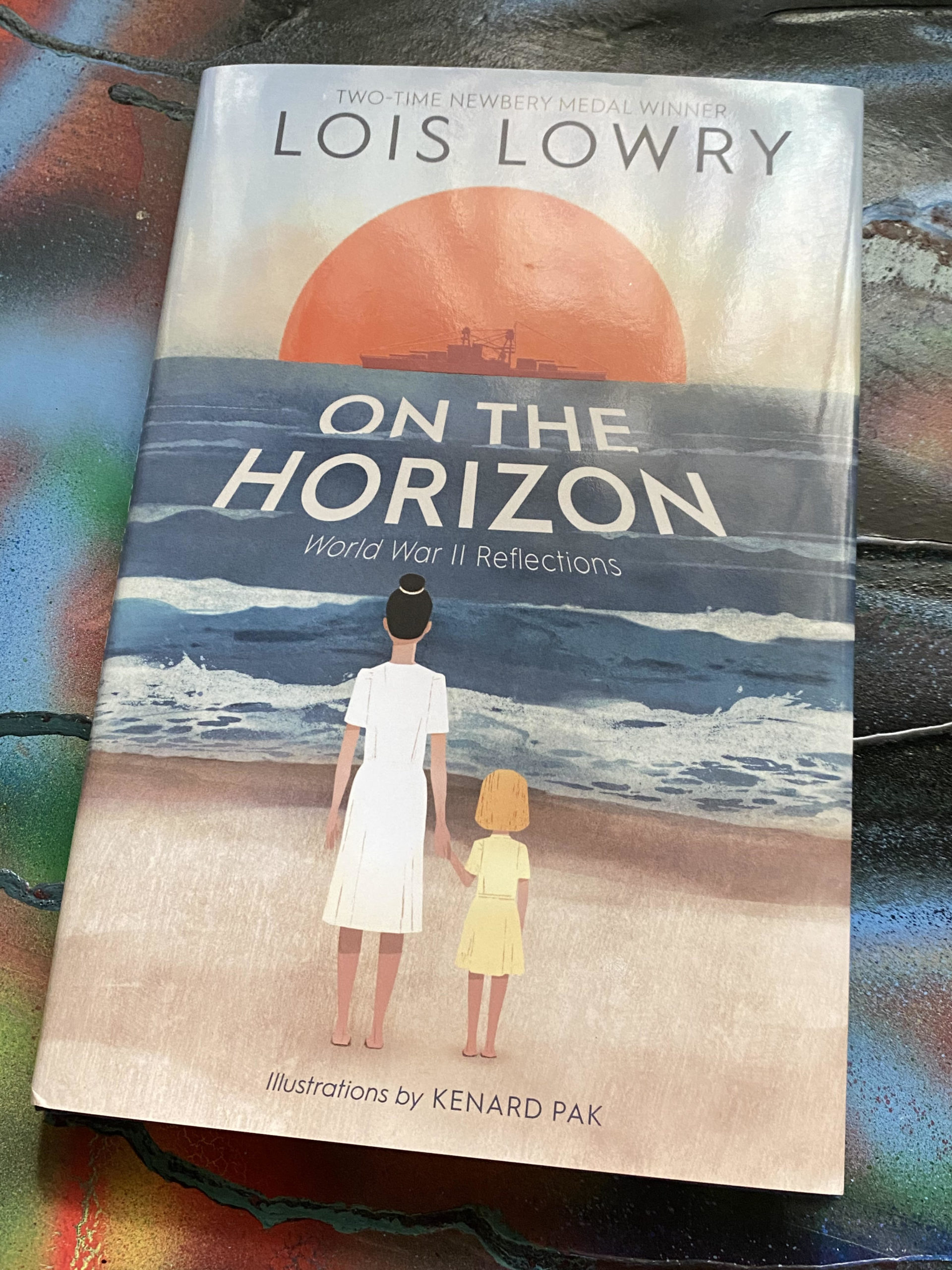

On the Horizon by Lois Lowry

(2020)

It turns out Tae Keller, 2021 recipient of the Newbery Medal, is not the first Hawaii writer to win the award. Lois Lowry, who won the medal twice, was born in my home state in 1937 and lived here for a couple of years. As a pre-teen, she moved with her family shortly after World War II to Japan.

Lowry mentions these connections in an author’s note at the back of On the Horizon, a collection of poetry set mostly in 1941 Hawaii and 1945 Japan, telling the stories of people touched by both sides of the war in the Pacific: the beginning and end, the United States and Japan.

Writing poetry for children is supremely difficult. Make it too artsy and it never connects with its audience. Make it too explainable and it loses poetry’s ineffable magic. I’ve seen very few collections that hit the sweet spot consistently, and On the Horizon doesn’t quite do it either.

It’s a really good attempt, though, as Lowry employs a few traditional forms of verse without being teachy or preachy. She sticks mostly to rhyme, but doesn’t settle into a ricky-ticky rhythm that would work against the sobriety of her subject. She’s writing about the deaths of young men in war, after all.

She does use a lilting, melodious voice when writing about her young self, and young readers will likely grab quickly onto these poems:

I wonder, now that time’s gone by

about that day: the sea, the sky . . .

the day I frolicked in the foam,

when Honolulu was my home.

But I appreciate other moments, as when Lowry personifies the ships (a centuries-old tradition) and plays with words a little:

Their places

(the places of the gray metal women)

were called berths.

Arizona was at berth F-7.

On either side, her nurturing sisters:

Nevada

and Tennessee.

The sisters, wounded, survived.

But Arizona, her massive body sheared,

slipped down. She disappeared.

Lowry makes it work, grouping poetry in three sections. “On the Horizon” contains poems set in Hawaii. “Another Horizon” contains poems set in Japan. A third section, “Beyond Horizons,” connects the first with the second in ways I won’t spoil, but the poetry in this last part is the reason to read this book, offering a collective thesis and theme. It’s rather devastating and lovely.

It’s also a keeper. Young readers will find second and third readings rewarding, especially if the grownups around them resist the temptation to unpack it all for them. Here’s hoping they do!

Three of five stars: I like it.